This is Part 1 out of 3 written by our Market Research Ops Analyst, Jason Lee, on how Researchers can ensure they are writing their studies in the best way to get better data.

Nudge Theory in Research

By Jason Lee

Surveys… we’ve all taken them a hundred and one times for a million different reasons. Chances are, you’ve recently taken one, and you didn’t think too hard about it. But have you ever considered that the wording of the question, or even the placement of the answers may have influenced your choice? That the mere BOLDING, underlining, italicizing of a phrase could drastically alter the way you perceive and answer a question?

In recent years, Nudge theory has gained popularity and renown worldwide in every aspect of life – from Silicon Valley tech companies to politics, and even to public health. This new-age theory in behavioral science, political theory and economics, suggests that indirect influence and subtle suggestions can be harnessed as ways to influence people’s behavior and decision-making.

Nudging provides an alternative to traditional ways of achieving positive results, such as through educating, creating legislation or enforcing through mandates or demands. After being published, Nudge theory was quickly accepted and has since influenced the way several political campaigns have unfolded in the US[1] and Great Britain[2]. Several “nudge units”[3] exist around the world at all levels from national (UK, Germany, Japan and others[4]) all the way to the international level (IMF, World Bank, United Nations).

We can define the ”Nudge” as all persuasive action leading up to the final decision a person makes. Also known as choice architecture,[5] the “Nudge” is described in The Journal of Consumer Research as the “design of different ways in which choices can be presented to consumers, and the impact of that presentation on consumer decision-making which then can alter someone’s behavior in a predictable fashion without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives.”[6] In layman’s terms, nudge theory doesn’t take away choices, or alter the reward at the end to achieve results. Instead, it uses certain methods of pushing the brain to make a certain choice, even without that person actively knowing they’re being influenced. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and “cheap” to avoid[7]. Nudges cannot be demands, mandates, or exclusions of choices.

To put this concept into perspective, if a supermarket wants customers to make healthier choices, they could place the fruit at eye level and move the junk food onto the higher or lower shelves. This would count as a nudge. However, if a supermarket were to refuse to carry junk food, this would not be a nudge, since the supermarket is now limiting the choices of the customer. [8]

Nudge theory has been widely accepted by fortune 500 companies for managerial practices, by governments to sway decision making, and even by local grocery stores to promote better patron health. So why hasn’t market research caught on? As researchers why are we not more frequently, and consistently using Nudge theory to create better questions, to ensure better results?

In light of all of this, you may be asking yourself “How can I incorporate this into my studies? How do I take this theory and apply it in the field?”.

Take a minute to think about the questions below. Do you have the answer?

“A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?”

A. $0.05

B. $0.10

C. $0.15

D. $0.20

Many people respond by saying that the ball must cost 10 cents. Is this the answer that you came up with? Although this response intuitively springs to mind, it is incorrect. If the ball cost 10 cents and the bat costs $1.00 more than the ball, then the bat would cost $1.10 for a grand total of $1.20.

But what if we change the formatting of the question? After reading these, do you have a different answer?

“A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?”

“A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?”

“A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?”

“A bat and a ball cost $1.10 IN TOTAL. The bat costs $1.00 MORE THAN the ball. How much does the ball cost?”

A. $0.05

B. $0.10

C. $0.15

D. $0.20

The correct answer to this problem is that the ball costs 5 cents and the bat costs — at a dollar more — $1.05 for a grand total of $1.10.

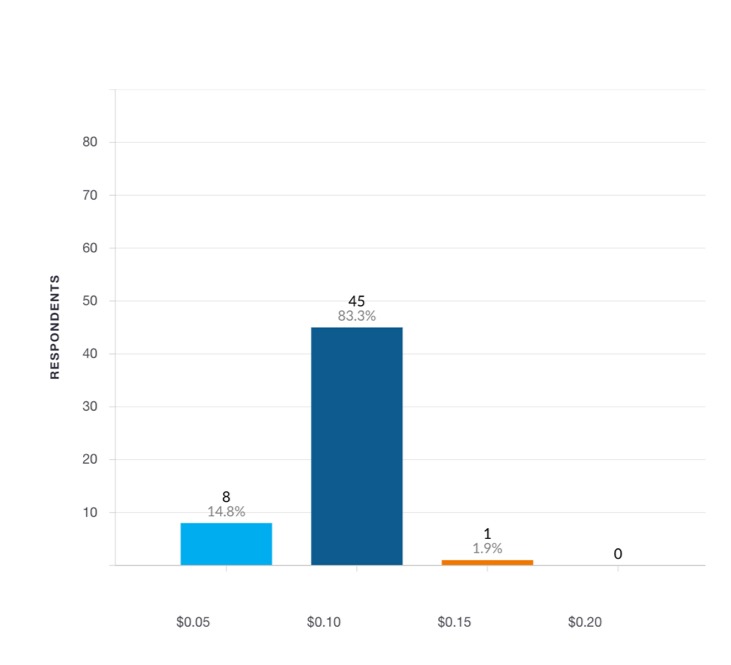

After running this study for 250 respondents on the Upwav platform, one can see that over 83% of respondent chose the incorrect answer when presented the question without formatting.

But why do so many people answer incorrectly? The answer is that people often substitute difficult problems with simpler ones in order to quickly solve them. In this example, some people seem to unconsciously substitute the “more than” statement in the problem (the bat costs $1.00 more than the ball) with an absolute statement (the bat costs $1.00). This makes the problem easier to solve.

Now that we know the above, is it possible for us as researcher to “nudge” the brain to slow down? Will that “nudge” result in answers that are far more likely to be correct and of a higher quality? Are there techniques which work better than others?

This phenomenon of irrationality, where the same questions/answers, simply formatted differently, with or without bolding, underlining, italics, or CAPITALIZATION will lay the groundwork of the next few articles to come. By the end of this series, I hope to have rattled your brain enough for you to ask the most important question as researcher: “How do I ensure that I’m asking better questions, so that I will receive the best possible data?”

Sources:

[1] Carol Lewis (2009-07-22). “Why Barack Obama and David Cameron are keen to ‘nudge’ you”. London: The Times. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

[2] “About us – Behavioural Insights Team – GOV.UK”. www.gov.uk.

[3] Ebert, Philip; Freibichler, Wolfgang (2017). “Nudge management: applying behavioural science to increase knowledge worker productivity”. Journal of Organization Design. 6:4.

[4] 5555, corporateName=Department of Premier and Cabinet; address=1 Farrer Place, Sydney, NSW, 2000; contact=+61 2 9228. “Behavioural Insights Unit – What’s new in the Behavioural Insights Unit”. bi.dpc.nsw.gov.au.

[5] Scheibehenne, Benjamin; Greifeneder, Rainer; Todd, Peter (2010). “Can there ever be too many options? A meta-analytic review of choice overload”. Journal of Consumer Research. 37(3): 409–25. doi:10.1086/651235. JSTOR 10.1086/651235

[6] Thaler, Richard H.; Sunstein, Cass R.; Balz, John P. (2013). Shafir, Eldar, ed. The Behavioral Foundations of Public Policy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 428–39.

[7] Saghai, Yashar (2013). “Salvaging the concept of nudge”. Journal of Medical Ethics. 39: 487-493. doi:10.1136/medethics-2012-100727.

[8] Kroese, F.; Marchiori, D.; de Ridder, D. (2016). “Nudging healthy food choices: a field experiment at the train station”. Journal of Public Health. 38 (2): e133-e137.